In Ruben Castaneda’s S Street Rising, a collection of personal accounts surrounding the crack epidemic of the ’80s and ’90s, he recalls crack exchanges outside a nightclub on the corner of S and 7th Street called John’s Place. I recently visited the location, now Angel’s Share Wines and Liquors, and got to witness how the building and neighborhood have developed and transformed from those described in Castaneda’s book. Standing there, imagining what the spot would have looked and felt like when John’s Place remained, I wondered about the context of the nightlife scene in Shaw in the 1980s, a now absent and forgotten culture. In further exploring this idea of a lost culture, of a Washington DC that no longer exists, I learned of the red-light district that once thrived on DC’s 14th Street. While the old red-light district of the ’80s was located in a different area of the city from John’s Place, both share the overarching theme of a forgotten Washington DC, one that has been reduced to fading memory. Today, like the club and bar culture that John’s Place represented, DC’s exotic dance and other sex-related industries that defined the downtown red-light district are gone. In 2005, Chris Vogel of the Washingtonian set out to chronicle the relatively unknown history in his article, “X RATED: DC’s Underground Sex Industry.” In this essay, based in Vogel’s article, I will discuss how DC’s red-light district disappeared, the consequences of that cultural change as it has manifested in the sex industry decades later, and the broader transformation of DC that it may suggest.

From the beginning of the text, the context for the article and the the subject of the informative discourse is stated clearly with the title: “DC’s red-light district is gone, and the strip-club scene is pretty tame. But the sex industry is going strong.” While the unknown, quiet prominence of the sex industry in 2005 DC is an arguably worthy exigence for the article to begin with, Vogel precisely addresses why the reader should care about the subject at hand and recognize a degree of urgency. This introduction sets the stage for how the reader should consider the history he provides, not just as a reminiscence of a culture that is now gone, but also as a narrative that brings light to the consequences of the loss of that culture.

Before Vogel delves into the underground sex industry of his 2005 present, he first frames the red-light district of the ’80s as he subjectively recalls it, and how it compares with the new, “pretty tame” strip-club scene. “Gone is the old red-light district along DC’s 14th Street, where neon lights led the way to peep shows, go-go clubs, and burlesque halls.” The way he describes the lost district’s culture is not pessimistic or adverse, but rather vibrant and outrageous: “There was also burlesque, with big-name headliners like Blaze Starr, who performed in sequined outfits and plumes of feathers, and comedians who filled in between acts.” The red-light district was self-aware and shameless, a truly exotic culture that, according to Vogel’s portrayal, did not seem to alienate or victimize the parties involved. Alternatively, Vogel characterizes the modern strip scene in a different light. Only a few nude-dancing clubs remain, and he claims that the strippers they employ are “about as exotic as cashiers at a suburban mall.” Indeed, while strip clubs are not completely absent from the public eye, the colorful culture of the 1980s red-light district has completely evaporated.

The major catalyst of the red-light district vanishing, as Vogel explains, was the implementation of laws and restrictions to systematically phase out the concentrated culture. “A freeze on liquor licenses for nude-dancing establishments” in the ’90s provided “a compromise between eliminating them and letting them expand,” and an amendment instituted that any clubs trying to relocate had to settle more than 600 feet from any residential building or other strip club, in order to prevent the type of concentration that defined the old red-light district. However, despite the measures to suppress and hinder the expansion of the nude-dancing clubs, Vogel still highlights the continued presence of a lucrative strip industry, concentrated in several American cities in particular. One way he illustrates that presence is with a relative example that puts into perspective the scope of the strip business in 2005. He quotes Angelina Spencer of the Association of Club Executives, who, when talking about Atlanta and its approximately 40 major clubs, says that “even a conservative estimate of the economic impact of such clubs translates to . . . far above the economic impact of the Braves, Hawks, and Falcons combined.” Given that the visible strip business had not ceased to thrive in various other major cities, there must have been something different about DC’s perception of its own strip and sex culture. While Vogel’s depiction of the red-light district seems lively, virtually harmless, and even fun, he elucidates the perception of DC’s lawmakers of the culture as toxic, and in need of removal from the public landscape.

Vogel continually develops the dichotomy of the changes over time in the nude-dancing and sex industries. The visibly positive effects come from the general trend of a less sleazy strip club experience that comes with stricter legislation. A club owner recalls, “there were fewer laws and less enforcement. You even had [then-mayor] Marion Barry accused of doing cocaine at the This Is It club in the mid-1980s. Washington has changed. The most important thing I tell my managers is that we have to keep our license, so we can’t do anything that would cause us to lose it.” It seems that the outward impact of legislation and cultural changes shows to be positive. On the other hand, a major byproduct of legislation that has suppressed the sex industry of the past is that it has forced such services to function clandestinely, which has led to the modern underground sex industry that prompted his writing. Thus, Vogel goes on to describe the “flourishing underworld of escort services and massage-parlor brothels” that is unfortunately “rife with victims.” He details the appalling story of Tina Frundt, a former prostitute who was sold into sex at age 10 and went on to suffer under the vicious control of a pimp that started as an affectionate partner. She was raped, beaten, and mentally tortured, brainwashed to believe that her misfortune was in some way her own fault. This account is only one of many examples Vogel includes to craft the whole reality of Washington’s sex industry, and, suddenly, it becomes increasingly apparent that the situation is quite nuanced and in many ways has not developed for the better.

Today, nearly 14 years after Vogel wrote this article, the dangerous underground sex industry of DC remains, and it seems to have compounded. A 2014 study by the Urban Institute valued DC’s underground sex industry at $103 million. Now, as the industry has continued to infest the city’s streets, the conversation has finally circled back to legislators. Ironically, decades after laws were passed to suppress DC’s sex-related industries, the unforeseen, tragic consequences have led lawmakers to address the animal that is the perilous hidden sex industry that victimizes countless innocent young people. David Grosso, an “at-large D.C. council member” has proposed a bill to decriminalize prostitution in order to combat the decentralized, unregulated system of sex trafficking that the strict laws of the 1980s have fostered. Last year, in light of a new election cycle for the DC Council, candidates received questionnaires about the proposed bill. One response from Martin Moulton of the Gay Libertarian Party read, “Only by legalizing sex work will private peaceful/non-violent/regulated business owners and entrepreneurs be free to create humane, safe and sanitary spaces for adult sex work” (Chibbaro). Indeed, the present state of DC’s sex industry is alarming and serious, and it poses an increasingly talked-about problem that needs fixing.

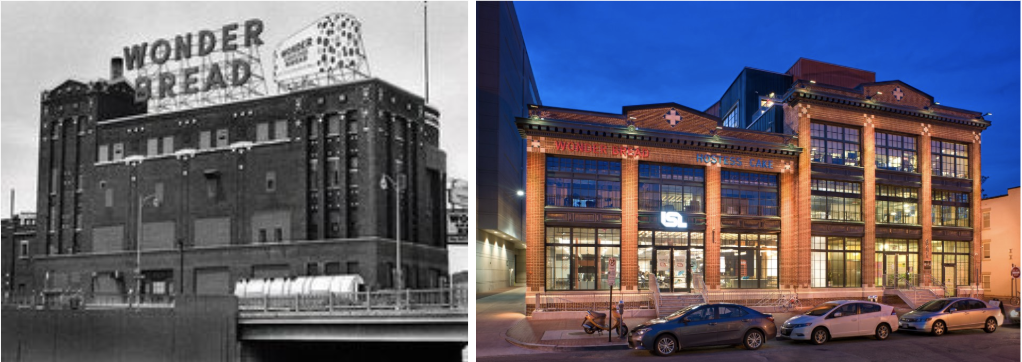

The common theme that seems to extend throughout the various avenues of cultural transformation in DC — whether it in be the strip and sex industries that once characterized the 14th Street red-light district, or in John’s Place’s Shaw versus that of today — is that well-intended efforts to “clean up” DC have had outwardly positive effects, but also underlying, unintended negative consequences. As a result, what has emerged is a disparity between public perception of such transformation and the reality for the victims of those changes that are left helpless. In Vogel’s article, he points out that “the gaudy downtown clubs have been replaced by office buildings.” This trend unmistakably parallels Shaw. The replacement of the red-light district and its many clubs with new structures like office buildings ostensibly indicate a progression towards a safer, more wholesome DC, but at the expense of the women that now serve a despicable underground sex industry. In the case of Shaw, the replacement of the John’s Places of the area, of other bars, nightclubs, businesses, and other establishments with a new wave of hip, contemporary bars and modern office spaces and residences has supposedly revived the once-crack-ridden neighborhood as up and coming and developing. However, the gentrification of Shaw has come at the expense of the historically black population that has lived there for decades. Rising housing prices that coincide with the influx of a white, affluent demographic are contributing to the widespread displacement of lower-income black residents that can no longer afford to live there (Gringlas). Therefore, the new and improved Washington DC, devoid of a red-light district and filled with avant-garde bars and nightclubs in Shaw, only really favors the elite that brought about the areas’ transformations, while alienating the populations that were there first.

Sources:

Chibbaro, Lou. “Will D.C. Decriminalize Prostitution?” Washington Blade: Gay News, Politics, LGBT Rights, Brown, Naff, Pitts Omnimedia, Inc. , 31 May 2018, www.washingtonblade.com/2018/05/31/will-d-c-decriminalize-prostitution/.

Gringlas, Sam. “Old Confronts New In A Gentrifying D.C. Neighborhood.” NPR, NPR, 16 Jan. 2017, www.npr.org/2017/01/16/505606317/d-c-s-gentrifying-neighborhoods-a-careful-mix-of-newcomers-and-old-timers.

King, Colbert I. “Washington D.C.’s Serious Sex-Trafficking Problem.” The Washington Post, WP Company, 15 Jan. 2016, www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/sex-slavery-isnt-just-a-problem-overseas/2016/01/15/bc3acb04-badd-11e5-829c-26ffb874a18d_story.html.

Koslof, Evan. “Sex Trafficking: It’s Happening Right Now in DC, & We Need Your Help.” WUSA, 10 Feb. 2018, www.wusa9.com/article/news/local/dc/sex-trafficking-its-happening-right-now-in-dc-we-need-your-help/65-516622896.

Stein, Perry. “Study: D.C. Underground Sex Industry Valued at $103 Million.” Washington City Paper, 12 Mar. 2014, www.washingtoncitypaper.com/news/city-desk/blog/13068407/study-d-c-underground-sex-industry-valued-at-103-million.

Vogel, Chris. “X RATED: DC’s Underground Sex Industry | Washingtonian (DC).” Washingtonian, 1 Nov. 2005, www.washingtonian.com/2005/11/01/x-rated-dcs-underground-sex-industry/.